Newfoundland and Labrador is the kind of place that stays with you long after you leave its jagged shores behind. It is a place where the expansive and intimate intertwine, where formidable landscapes are sprinkled with small, colourful communities nestled in coves and tucked away in sheltered harbours. It is a place where wind is made visible and fog is as much part of the landscape as the land and sea. It is a place that braids together stories of the Earth’s billion-year-old history and those of people who have called this part of the world home into a unique and distinct identity.

It is known by different names. Mi’kmaq, who have lived across Atlantic Canada long before Europeans “found” this land, call Newfoundland Ktaqmkuk, which could mean either “the larger shore” or “the other shore.” Newfoundland’s Inuktitut name is Ikkarumikluak (ᐃᒃᑲᕈᒥᒃᓗᐊᒃ), “place of many shoals,” while Labrador is called Nunatsuak (ᓄᓇᑦᓱᐊᒃ), meaning “the big land.” With many of its early settlers coming from Ireland, the island also has an Irish Gaelic name – Talamh an Éisc, “the Fishing Grounds” or “the Land of Fish.” The Norse, the first Europeans to reach the shores of North America, referred to it as Vinland, the name that covered Newfoundland as well as Nova Scotia and coastal New Brunswick, while calling Labrador Markland.

People continue to flock to Newfoundland and Labrador’s shores: some in hopes of making a home here, others, like us, just visiting, at least for now. This was our second trip to Canada’s easternmost province. (Read about our first visit here and here). We returned to some familiar places and visited new spots. Three weeks, six ferry crossings, many vibrant communities, numerous challenging trails, and never-ending breathtaking vistas later, we’ve fallen deeper in love with this incredible place.

Newfoundland and Labrador is the kind of place that stays with you long after you leave its jagged shores behind.

Inside Out

We get off a ferry at Channel-Port aux Basque around seven on a warm Saturday evening. From here, it’s a four-hour drive to the Trout River campground in Gros Morne National Park. With a stop for gas and food, it takes us closer to five. By the time we arrive, it’s already after midnight. To our surprise, the light is still on at the registration booth. Park staff welcome us with a warm: “You made it!”

Luckily, we don’t need to set up camp since we have booked an oTENTik, a permanent canvas structure that comes with beds, a table, and a heater, which we do use even though it’s the middle of July. We get our sleeping bags out and go to bed.

The next morning (and I am using the word “morning” very loosely here), we are ready to explore. Our plan is to hike the Tablelands, the area of the park that features exposed mantle. Half a million years ago, when ancient continents collided, it was thrust up, and now we get to walk upon a layer normally found deep inside the Earth – an otherworldly experience. This alien-looking, barren landscape is composed of peridotite, which doesn’t support the growth of many species. But once we look closer, we notice all the plants that have adapted to the harsh environment and made the Tablelands their home.

The Tablelands in Gros Morne National Park are one of the few places in the world where you can walk on exposed mantle, a layer normally found deep inside the Earth.

Because we start the hike so late in the day, we don’t have time for the entire Tablelands off-trail loop (again). The Bowl is the farthest we get. This giant circular dip carved by glaciers still holds on to the remnants of winter. A couple of kids are playing around in a patch of snow.

“Have you tried the Newfoundland slushie?” their father calls out to us with a laugh.

On our way back to the campground, we stop at a convenience store in Trout River to get ice for our cooler. We end up buying a pair of stripy knit socks.

“You definitely won’t need them today?” laughs the shopkeeper. She is right. It is a hot, cloudless day with temperatures in upper twenties.

“I love these socks,” she adds. “My mom knits them.”

“And I am buying them for my mom,” says my husband. “So, your mom made socks for my mom.”

After dinner, I head to the Trout River Pond. The beach is a network of moose tracks. These are the only signs of the supposedly omnipresent animal that we are going to see during our entire trip. Last time we visited, we saw a moose, or several, almost every day.

As much as I’d like to catch a glimpse of a moose, it’s not why I am here. The Tablelands rising on the other side of the pond look best in the evening light. The setting sun bounces off their slopes and brings out the oranges and reds. After many pictures and a few conversations with fellow campers that wander onto the beach to enjoy the view, I finally pack my equipment and head back to our oTENTik.

The Tablelands across the Trout River Pond look best in the evening light.

Of Fog and Flies

Labrador welcomes us with fog and writes its farewell in raindrops.

When we were planning our trip, we considered driving the entire Expedition 51 route through Labrador. Eventually, we decided to leave that adventure for next time. For now, we just dip our toes in Labrador’s waters – proverbial, of course, because we are not brave enough to get into the ocean.

After an almost two-hour ferry crossing from St. Barbe, we emerge on the other side of the Strait of Belle Isle at Blanc Sablon. After that, it’s about 45 minutes to Pinware River Provincial Park where we have a campsite booked. The campsite gets top scores for location and views. A short path connects it to the beach, and we can see the ocean over grassy sand dunes. On the downside, by the time we manage to drive tent stakes into very hard ground, we each acquire a faithful following of black flies. They stay with us for most of our time in Labrador, occasionally getting chased away by wind or thick fog. Every morning, we emerge from our tents, and for a few blissful seconds believe, against all previous evidence, that today will be a fly-free day. But then they descend one by one coalescing into a thick cloud, darting and zooming around looking for exposed flesh. At night, we take stock of the bites, and in spite of itchiness, admire how much damage a creature this small can inflict.

Our campsite at Pinware River Provincial Park comes with beautiful views of Strait of Belle Isle and clouds of black flies.

Just like the flies, the fog hangs around. On our first morning in the park, as we drink coffee on the beach desperately trying to ignore persistent attention of our new friends, we watch long, gauzy tendrils seep into the land and wrap themselves around dense trees and moss-covered rocks, filling the air with chill and moisture. It rises in columns from the sea until it’s no longer clear if the fog is born out of the water or the other way around.

Fog erases the boundary between land and sea.

Our first stop the next day is the Red Bay National Historic Site and UNESCO World Heritage Site. For about 70 years in the 16th century, this shore drew whaling expeditions from the Basque region of Spain and France. The journey across the Atlantic was long and treacherous but whale oil was a valuable commodity used to light lamps across Europe. Eventually, Basque whalers abandoned the site, but they left behind traces of their presence scattered around, various artifacts, even a chalupa (a small whaling boat) preserved in the silt and freezing waters of the Strait of Belle Isle. Among those artifacts are red clay roof tiles they brought with them. We see piles of them scattered around a very foggy Saddle Island as we take a guided tour with a Parks Canada ranger.

Saddle Island, a short boat ride away from the mainland, is where Basques set up their whale oil processing operations back in the 16th century. The wreck on the right is Bernier, which sank in 1966; resting under the water is a galleon loaded with eight hundred barrels of oil. Believed to be the San Juan ship toppled by storm in 1565, it was discovered in 1978; a small whaling boat – chalupa – was hidden under it. The chalupa and artifacts from the ship are now on display at Red Bay Visitor Centre.

After we finish the trip to the past, our small group, which in addition to us includes a woman doing the Expedition 51 and a family from Switzerland on a cross-Canada trip, gets to more present matters.

“Where is the nearest gas station? Where can we get groceries?”

The park ranger chuckles, then turns to her colleague:

“Did you hear, Mike? They are asking me about gas and groceries.”

They both laugh as if it’s an inside joke.

“Gas is about half an hour that way,” she says. “But if you are travelling further north, then the next gas station is in two hours. For groceries, you will have to drive back 45 minutes or so.”

During the tour, the park ranger keeps repeating “Imagine what life was like for Basque whalers and Innuit back then.” I keep thinking what life must be like for people living here today in this breathtaking yet often unforgiving land, where help and supplies can be hours away and you can often rely only on yourself and your neighbours.

A waitress at the Whaler’s Restaurant, where we end up after the tour, along with the rest of our group, says “That must be very different” when we tell her we are from Toronto. Very different indeed.

We later climb to the top of Tracey Hill – 689 steps peppered with inspirational quotes. Even partially obscured by fog, the scale of this place is unmistakable. No wonder, they call Labrador the Big Land. Its spaciousness overwhelms. Limitless, it unfurls in every direction challenging our three-dimensional perception. With no edge or end in sight, it dips into infinity.

We take 689 steps, many featuring inspirational quotes, to the top of Tracey Hill for some beautiful views of Red Bay and the ocean.

We fall asleep to a soothing lullaby of the ocean.

“We can say we vacationed by the sea in Labrador,” says my husband.

“You make it sound so glamourous,” I laugh and think about the black flies that will greet us outside our tent tomorrow morning.

A lone loon yodel breaks through the seagulls’ piercing cries. “Do loons live in salt water?” is my last thought before I drift away into a realm of dreams. (In case you are wondering, they do. We see more of them later.)

Carlos Vives’s “Ella Es Mi Fiesta” wakes me up at 4:45 a.m. the next day. When I set it up as my alarm a few years ago, I was hoping it would help turn the start of each day into a party. But the only party that’s on my mind right now is the welcome one that may be awaiting outside. I do, however, want to catch a sunrise in Labrador, and with the rain and clouds returning the next day, this is my only chance. After some deliberation, I cover as much of my body as possible and step outside. I brace for an attack, but it doesn’t come. I guess black flies aren’t into sunrises.

I walk along the beach to the confluence of Pinware River and the Strait of Belle Isle. The sky is cloudless. There are no dramatic colours, just a strip of orange and a few pink whisps slowly dissolving into the blue of the sky as the sun emerges from behind the hills. Right on cue come the flies. After another half an hour of wandering on the beach, I retreat into the tent. Just a few more minutes of fly-less peace before we get to making breakfast.

I wake up early to enjoy the sunrise and discover an unexpected benefit – no black flies or, at least, very few.

(By the way, we have a bug shelter – a solid one from Eureka that we got at the outdoor adventure show. We even try to set it up on our first morning. With nothing but shrubs around and surface hard as rock, it isn’t an easy task, and the result is flimsy and laughable. As the wind picks up, we decide it’s too risky to leave it like that and take it down before heading to Red Bay. Good thing too. When we return, one of our tents is lying flat on the ground with rainwater pooling in folds and creases. Not too hard to imagine what would have happened to our barely attached shelter. The next day, when faced with a choice between black flies and going through the set-up process again, we choose the flies.)

We miss a boat tour with Whaler’s Quest. We watch the vessel disappear on the horizon as we pull into Red Bay. We regroup and drive to Point Amour Lighthouse, the tallest in Atlantic Canada. The day is warm and Forteau Bay is surprisingly devoid of black flies. As we stroll around the coast, we start shedding our many layers. Seal heads are bobbing in the water. Remnants of HMS Raleigh wreck are scattered along the shore. The rocks exposed by low tide are meticulously arranged in a pattern that almost looks man-made. We will later learn that these are Archaeocyathid reefs. Formed about 530 million years ago, they are evidence that this region was once a warm shallow sea near the equator.

Point Amour Lighthouse is the tallest in Atlantic Canada.

A guide in pink crocs takes us to the top of the lighthouse. A tour bus has just pulled up so our group is large, and the narrow circular stairs are tight. The guide stops on each landing to share some lighthouse trivia and give everyone a chance to catch up.

“How many times a day do you have to do the climb?” I ask her.

“Depends on the day. If we get a lot of tours, it can be up to ten.”

I do the math in my head: 132 steps times ten – that’s quite a workout.

“No gyms around here,” she adds. “So this works well for me.”

On the way back to our campsite, we hit Bousquet’s Hill trail in West St. Modeste. Just like the Tracey Hill trail we did yesterday, it is a boardwalk with some steps. There are no inspirational quotes though. And no wind, which means, you guessed it, flies. They help us get down to the car in record times.

Bousquet’s Hill trail: more steps, more incredible views, more black flies.

On our last night in Labrador, right before the sun slips behind the trees, a giant rainbow spans the sky. It drinks water from the sea, then distills it into an arching ribbon, a perfect blend of colours born out of the union of water and light.

A beautiful rainbow on our last night in Labrador – an amazing parting gift from The Big Land.

Norse, a.k.a. Great Northern Peninsula, Sagas

We take our camp down early to avoid black flies. The ocean is once again swallowed by the fog. By the time we are cramming our gear into the car, flies appear, sleepy yet determined to give us a proper send-off. By 7:15, we are sitting at Dot’s Café and Bakery in L’Anse au Loup, one of the few places to get food around here. It’s the earliest we’ve managed to leave the campground. We call it the black fly effect.

We finish our breakfast and drive to Blanc Sablon. There is an hour to spare before boarding the ferry so we stop at La perle rare LBS café to get more coffee. We leave with a package of Tuckamore Blend from Gros Morne Coffee Roasters, one of many we will buy on this trip.

It starts raining by the time we get on the ferry. The rain follows us across the Strait of Belle Isle and up the wiggly coast of Newfoundland. We finally manage to shake it off somewhere between the Flowers and Pine Coves. When we arrive at Gunners Cove to be transported to our cabin across the bay, the sea is a calm stretch of blue. It matches the blue of the sky now peeking through the clouds, miles away from the greyness of this morning.

Our home for the next few days is called A Little Drop of Sea, a bright-blue cabin that sits on the other side of Gunners Cove. The only way to get there is by water or on foot, if you are willing to do a long trek around the bay. My husband and younger son take the kayaks. The other part of our family along with all our supplies gets to ride in a boat with Rick, the owner’s father.

A Little Drop of Sea cabin in Gunners Cove – a perfect setting for my birthday.

“I built it myself back in 1997 when kids where little,” says Rick as he gives us a tour of the cabin. The walls are decorated with pictures of his grandkids, one proudly displaying a crab, the other one holding a starfish, both smiling. The place is soaked in memories and salty air.

“I later sold it. But then my daughter called and said she’d bought it back. You, poor soul, I said, how are you going to manage it?” continues Rick.

“You get a lot of visitors though?”

“Oh, yeah, we are busy,” he smiles.

I can see why. The solitude, the love put into every detail, the views, a beautiful verandah with big windows to enjoy those views even on a chilly or rainy day – a perfect setting for my birthday.

Rick rides away in his boat after giving us instructions. It’s still early in the day so we go kayaking around the cove. With the next two days bringing rain and wind, we won’t be able to take the kayaks out until the morning of our departure.

The cabin is accessible by water only. On our first day, we take advantage of calm seas and go kayaking around the cove.

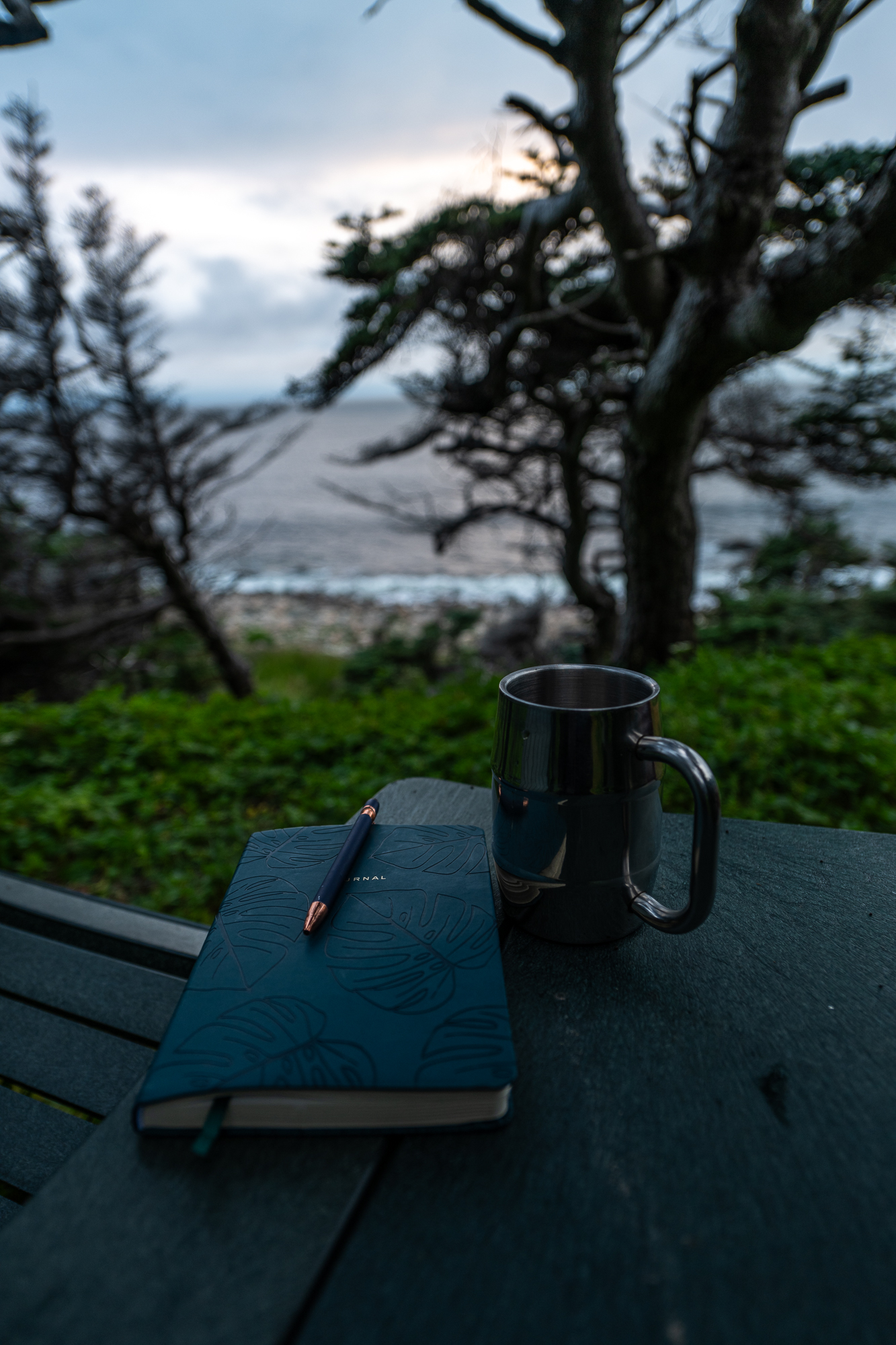

My birthday starts with fog, progresses to rain, then ends with a gorgeous sunset. I spend the day on the verandah – reading, writing, taking photos, daydreaming, just hanging out with my family, eating good food and drinking good coffee. My kind of celebration. The brightly coloured houses across the water drift in and out of view. I will later learn that the blue one is 150 years old and it once belonged to Annie Proulx, a Pulitzer Prize winner for her novel The Shipping News and author of Brokeback Mountain, a short story later adapted into a motion picture. I am excited to know that I’ve been breathing the same air as a famous writer. I order The Shipping News from my local bookseller as soon as we get home.

My favourite part of the cabin is the verandah. That’s where I spend my very foggy and rainy birthday – reading, writing, taking photos, daydreaming, just hanging out with my family, eating good food and drinking good coffee. The day ends with a beautiful sunset.

The next morning, Rick comes to take us across the cove so we can do some exploring. L’Anse aux Meadows is first on our list. It is a small community of 13 people at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula. It is also a National Historic Site and UNESCO World Heritage Site, famous thanks to the people who visited it over a thousand years ago. It’s here that Norse expeditions from Greenland landed and built an encampment of timber-and-sod houses. Norse Sagas talked about the voyages but it wasn’t until 1968 that discoveries by archaeologists Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad proved that the place referred to as Vinland was indeed Newfoundland.

L’Anse aux Meadows at the tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula is the only authenticated Norse site in North America. Leif Erikson and crews of Norse explorers built an encampment here over 1,000 years ago. They called the area Vinland.

“L’Anse aux Meadows was a seasonal base camp, although occasionally the Norse would spend winters here as well. You are probably thinking: Why would they stay here in the winter?” says a cheerful park ranger, a self-described proud Newfoundlander, who sprinkles her tour with questions and jokes.

“But think where they came from. For them, this was practically a resort.” She pauses for greater effect. “So, I say they were the first snowbirds, am I right?” comes the punchline.

Our group huddles together to get some protection from the wind. Nothing about today’s weather speaks resort. The tour continues. The guide takes us through archeological remains of various structures – mostly depressions in the ground. Through her stories, she brings the world of the Norse back to life.

“Norsemen only owned about a kilo and a half of iron in their lifetime,” says the guide after explaining how resource- and labour-intensive iron production was. “What would you make if you had this much iron?”

“A sword,” shouts a man at the back.

“And how would you build a house with a sword?” parries the guide. “Not a very good provider. Just saying.” That last comment is directed at the man’s wife. Everyone laughs.

The correct answer is an ax. It can be used both as a tool and a weapon.

Once the tour is over, we huddle around a fire inside the reconstructed Norse house made of sod and wood, a welcome reprieve from the biting wind. Park employees dressed as the Norse regale us with stories of their life, play musical instruments and demonstrate textile-weaving.

A reconstructed Viking village at L’Anse aux Meadows offers a glimpse into the Norse life during their stay in Vinland.

Just like the Basque whalers that will arrive to the coast of Labrador 600 years later, the Norse came to these shores for resources, primarily timber and bog ore. Their presence was short spanning no more than three decades. It is, however, an important chapter in the story of human migration, a meeting point of two worlds as the Norse encountered the Beothuk and Innuit, who had lived here for millennia. Subsequent European arrivals will have more devastating consequences for Indigenous people, leading to colonization, forced assimilation, and extinction of the Beothuk.

The Meeting of Two Worlds sculpture at L’Anse aux Meadows

Before leaving L’Anse aux Meadows, we tackle the Birchy Nuddick trail. Although “tackle” is probably too big of a word for this mostly flat trek that winds through boggy areas, past tuckamores, along rocky shores of Strait of Belle Isle. We come across a few small houses. They are called “álfhól” and are built in Iceland for the Huldufólk, or “hidden people,” who are believed to be elves. I look for something to add to an already generous collection of presents by the door. In my camera bag, I find some shells from our trip to California a couple of years ago – a fitting gift for elves.

Views along the Birchy Nuddick trail: the same views the Norse enjoyed a thousand years ago, although they probably didn’t have the Parks Canada red chairs.

We drive back to Saint Lunaire-Griquet for lunch at the Daily Catch restaurant, one of the few places around here that don’t have ‘Norse’, ‘Viking’ or ‘Valhalla’ in their names. We follow with a homemade ice-cream at Dark Tickle. Made from local berries and served in a sculpin cone, it is delicious. So is their partridgeberry latte. We manage to squeeze in a quick hike along the Cape Raven Trail before catching a ride back to the cabin.

Cape Raven Trail takes us through a tuckamore forest to the edge of cliffs.

As Rick drops us off, he hands us a bag.

“Iceberg ice. I got it off an iceberg right in this cove earlier this year,” he explains. “It’s 10,000 years old.”

Last time we visited, we got a glimpse of a small iceberg somewhere around the Great Northern Peninsula. This time, even though we came earlier in the year, this present from Rick will be our only encounter with frozen visitors from the North.

Large Mountain Standing Alone

We arrive at the Green Point Campground in Gros Morne National Park shortly after sunset. Our four-hour drive from Gunners Cove has turned into nine with many stops along the way.

“We have plenty of time,” my husband keeps repeating with each unplanned detour. In the end, we have just enough to set up our tents before darkness and rain descend.

Our first stop is the Fishing Point Park at St. Anthony or “Snatnee”, according to the locals. Last time we came here, we saw a pod of whales right by the shore. We secretly hope that they will still be around but, I guess, no one has informed them of our arrival. We stop at a souvenir shop to buy a sticker for our food barrel. We end up buying another bag of Gros Morne Coffee, this one is called Long Range. A clerk at the store urges us to stop at the Rebel Coffee House. A small yellow shack by the side of the road packs a lot of charm and serves some of the best coffee we have tried so far. My husband proclaims it comparable to the Lusk coffee, which is a very high praise coming from him. (Lusk is a small town in Wyoming. Last year, we stopped there at a closet of a coffeeshop; it has since become the standard by which all coffee is measured). We walk out with another package – Dark Fog, which brings our Gros Morne Coffee Roasters count to three. We will pick up two more bags – Tablelands and Writers’ Roast at their headquarters in Deer Lake.

Fishing Point Park in St. Anthony: sadly, there are no whales like last time, but the views are just as impressive.

The next stop on our route is Port aux Choix, a national historic site that tells a story of Maritime Archaic, Dorset, Groswater and Beothuk peoples. We arrive after 5 on a Sunday. The visitor centre is already closed. But it’s not the only reason we came. The last time we visited, we saw woodland caribou wandering around. Unlike the whales in St. Anthony, the caribou are still here. In fact, there are more of them – a whole herd grazing by the sea.

A herd of woodland caribou awaits us at Port aux Choix.

“It was a good decision to come here after all,” repeats my husband as drive to the Anchor Café for dinner. After that, only a quick stop at the Arches Provincial Park separates us from the Green Point Campground, our destination for the night.

Arches Provincial Park, our last stop on the way to Gros Morne

When we were planning the trip, many locations were added and removed from the list, except for one. A visit to Gros Morne National Park was non-negotiable. After our trip eight years ago (read about it here and here), we knew we had to come back. We discussed doing the Long Range Traverse backpacking trail, then decided to leave it for another day. We then considered a hike to the Top of West Brook Pond Gorge, but it is only accessible with a BonTours guide and, at $325 per person, is not exactly affordable.

Now that we are here, we decide that the Gros Morne Summit Hike, a 17-kilometre trek to the top of Long Range Mountains’ second highest peak, is a challenge enough. We add visits to some familiar spots, like Lobster Cove Head Lighthouse, Green Point and Norris Point, but other than that, we don’t do much.

In Gros Morne, striking landscapes are depositories of geological and human history.

It isn’t just complaints from my husband that I cram too many activities into our road trips that inspire this more laidback approach to our trip. Our beautiful site at the Green Point Campground with two Muskoka chairs overlooking the ocean has “kick up your feet and smell the roses” written all over it. Quite literally because wild roses are everywhere. And so are wild strawberries. These tiny heart-shaped drops of red significantly slow down our already relaxed pace on trails. We pick them until our fingers are stained and my night dreams are filled with berries. One morning we get a bowl of these delicious delights right down by our campsite, add some blueberries we got during our hike to Gros Morne Mountain the day before, plus a few jars of local jam from a gift shop at Norris Point, and the French toast breakfast becomes the most sumptuous feast.

Our campsite by the ocean at the Green Point Campground had all necessary ingredients for a relaxing stay.

Speaking of the Gros Morne Mountain hike, it starts on a sunny, if a little chilly, morning. As we finish the 4.5-kilometre approach section, it gets warmer, and we shed a few layers. I even consider unzipping my pant legs. We begin our climb to the top, and I quickly realize how premature that would have been. Somewhere along the way we start putting the layers back on in whatever order we can locate them in our backpacks. Eventually, we end up with sweaters worn over windbreakers because the mere thought of taking them off to put sweaters on is chilling. Our plans to have coffee at the top are swept away by the wind, so cold and biting that all we can think about is to get off the mountain. We stop at the Ferry Gulch campsite instead.

Gros Morne is the second highest peak in the Long Range Mountains and the namesake for the entire park. Its French meaning is “great somber,” which is often interpreted as “large mountain standing alone.” Getting to its very cold and windy summit requires some work. But look at the views!

Unlike the ascent to Gros Morne Summit – 500 metres of almost vertical climb over scree, the trail down is gentler and significantly longer. We hike past green mountains, dotted with lakes that balance precariously along the edges, past waterfalls tumbling down vertical cliffs, above long narrow fjords, called “ponds” around here, and winding rivers that thread their way through glacier-carved valleys. By the time we get back to the approach section, fog erases the Gros Morne Mountain from view.

The trek down from the summit is longer but less steep than the ascent. It winds its way past green slopes of Long Range Mountains, glacier-carved valleys, lakes and waterfalls.

We meet the same groups of people on the trail. At times, we pass them, then they pass us in a game of trail tag. Eventually, we start talking and exchanging stories. We run into a couple of them during our relaxing stroll along a very flat Coastal Trail the next day.

“You picked an easy one today,” they joke.

A very relaxing Coastal Trail runs past meadows, bogs and groves of tuckamores – gnarled, stunted trees shaped by the wind and the ocean.

After our hike to Gros Morne, we end up at the Green Point Campground kitchen shelter. It is a place of connection, and not only because it has wifi. In the evening, after a day of explorations, people start trickling in to drink tea, play card games and share their stories. We meet a family from New Brunswick. They tell us about their Green Gardens hike. We tell them about black flies in Labrador. These little bloodsuckers are already becoming the stuff of legends.

The next morning, we head to the Green Point Geological Site, only a short walk away from our campground. These beautifully layered rocks formed on the bottom of an ancient sea more than 500 million years ago are a geological benchmark for the boundary between the Cambrian and Ordovician periods. They are also an invitation to see time differently. As I study these intricate formations layered like pages in a book, I think of all the new stories we will bring with us from this trip, all the new layers added to our lives. Some are briming with sheer awe of the Earth’s impressive genius so clearly on display in Newfoundland and Labrador. Other stories are more intimate, born out of human interactions with the land and each other.

Beautifully layered rocks at Green Point Geological Site hold stories of the Earth’s fascinating past.

To read more of those stories, check back soon for part II of our Newfoundland adventures.

Quite a trip. The morning mist pictures and the rock formations at the end were the highlights for me. I don’t like the sound of those flies.

LikeLiked by 1 person