The hardest part of writing about a long road trip is distilling several weeks of travels into a post of manageable length. I know I am way past manageable. But once I started the story of our Newfoundland and Labrador adventures, it quickly acquired a life of its own. It became less of a list of best places to visit and things to do, and more of a collage, a collection of tales, a quilt of memories and emotions inspired by the land, the sea and the people who call it home.

Our Newfoundland and Labrador trip is a collection of tales, a quilt of memories and emotions inspired by the land, the sea and the people who call it home.

Part I ended with our stay in Gros Morne, the last stop on Newfoundland’s west coast. It felt like a good place to pause and leave our more easterly explorations for Part II. So here we are driving to Dildo Run Provincial Park (yes, that’s what it’s called, although I should probably mention that “dildo” refers to an oar peg in a dory). The park is fairly small but we get a cozy campsite near the water, which we mostly use as a base to visit Twillingate and Fogo Island.

Dildo Run Provincial Park comes with an interesting name and beautiful campsites.

Art Born Along the Edges

Twillingate is known as the iceberg capital of the world. We are too late for icebergs though. And yes, there is a lot more to see and do in this beautiful seaside town (which we did during our first trip to Newfoundland). The main reason we are here today is the Twillingate-NWI Dinner Theatre. This almost two-hour show that comes with the most delicious meal is an upscale version of Newfoundland’s famous dinner party. It is a love letter to the island, a showcase of musical talents, community spirit and sense of humour – all the things essential to surviving and thriving in this harsh land.

The Twillingate-NWI Dinner Theatre Show is a love letter to Newfoundland.

We end up at a table with an older couple from L’Anse au Loup in Labrador. We excitedly tell them that we just came from there. They seem surprised when we, predictably, complain about black flies.

“We thought they weren’t that bad this year. But then we have been gone for a few weeks now. And after living there for a while, you don’t notice them as much.”

I don’t know how long I would have to live there to stop noticing them, I think to myself.

“You could have stayed at our house,” says the wife when she learns we camped in a tent. Famous Newfoundland and Labrador hospitality in one sentence.

The next morning it’s an early wake up call for us to catch a ferry to Fogo Island. Dildo Run doesn’t have many black flies, but mosquitoes pack a good punch, and unlike the flies, they are early risers. We quickly finish our breakfast to their persistent buzz.

All the posts I read in preparation for the trip recommended arriving at least an hour early for the Fogo Island ferry, which is only available on the first come, first serve basis. In spite of our best efforts, we come about 40 minutes before the 8 a.m. departure but, luckily, still make the cut.

Fogo Island lives up to its name. (I am referring to the “fog” part in Fogo because the name, actually, comes from the Portuguese word for “fire.”) After a 45-minute crossing, we emerge into a cloud spread on the ground. Our first stop is a coffee shop. At the recommendation of very helpful staff at the information centre, we drive to Punch Buggy Café in the town of Fogo. Its bright pink exterior is hard to miss. There is no indoor sitting and with rain intensifying, we drink our coffee in the car. It is predictably delicious. We start to develop a theory of coffee – the smaller the place, the better the coffee.

Fogo Island lives up to the “fog” part in its name.

Fogo Island is famous for many things, with Fogo Island Inn and a thriving art scene at the top of the list. And, if you believe our planet is flat, you would also know it as one of the four corners of the Earth. Above all, Fogo Island is a story of a community that had to re-invent itself after the industry it had relied on for centuries – cod-fishing – collapsed. At the centre of the story is Zita Cobb. Born and raised at Fogo Island, she made a fortune in tech industry and then returned to invest it in her community. Together with her siblings, she established a nonprofit social enterprise Shorefast, which encompasses several projects and community businesses. Among them are The Storehouse Restaurant (the best food we’ve had during our entire trip) and Growlers Ice-Cream (their partridgeberry jam tart ice-cream is out of this world). The enterprise has now grown into a national initiative – The Shorefast Institute for Place-Based Economies.

The centrepiece of Zita’s efforts is Fogo Island Inn, a 29-room resort that involves local community every step of the way: from preparing food to making furniture and quilts for beds. And while we could never afford to stay there, even for one night, it’s hard not to admire this majestic building, rising like a ship above the rocky shore.

The beautiful Fogo Island Inn involves community every step of the way: from preparing food to making furniture and quilts for beds. Staying here, though, is not cheap.

Then there is the art – international artist residency studios, galleries and shops are around every bend.

We pull by Fogo Island Metalworks in Shoal Bay and the first thing we notice is a giant metal squid overlooking the ocean next to a dragon fly and whale’s tail. There are also turkeys – not metal ones, actual live turkeys gobbling in a shed – and a garden. The squid will turn out to be the Kraken, a legendary sea monster from the Norse mythology. Marc Fiset, an artist behind Metalworks, draws a lot of inspiration from myths. He shows us his work in progress – “The Ferryman” of the Greek underworld who transports souls of the dead across the river Styx. The sculpture is to be unveiled the next day at the Burning Rock Festival, which Marc started a few years ago. We won’t be here so it’s exciting to get a sneak peek. Marc tells us about retiring to Fogo Island after his career in the military. We discuss our shared appreciation of dragon flies. And my husband asks about the process used to attach copper suction cups to Kraken’s steel tentacles. (For those not versed in metallurgy, like me, you can’t weld copper to steel.) We later find a metal sculpture of fish at Quidi Vidi Village in St. John’s. My husband immediately identifies it as Marc’s work before we even read the sign. The sculpture is called “The Fishery” and is indeed made by Marc Fiset together with fellow blacksmith Ian Gillies.

Beautiful creations by Marc Fiset of Fogo Island Metalworks

Our next stop is Fogo Island Saltfire Pottery. Beautiful mugs, dishes, pots, and sculptures of local wildlife line the shelves of this small shop in Barr’d Islands. A couple of great auks sit by the window next to a whale arching its back, ocean lapping right outside. These beautiful creations by Lee Danisch and Fraser Carpenter are all made on site in a traditional salt kiln.

Fogo Island Saltfire Pottery is filled with whimsical creations by Lee Danisch and Fraser Carpenter.

“How do you even choose?” the woman next to me voices my thoughts.

“There was a man here earlier. It took him an hour and a half to pick a mug,” replies a friendly woman behind the till.

It takes us less than that – about thirty minutes – to settle on a delicate teal dish in the form of a scallop shell.

After a few more craft shops, we decide we’ve got enough Christmas ornaments and jam. By now, the rain has stopped so we hit the Joe Batt’s Point Walking Trail. We make our way along the jagged shore, past a playground and community gardens, until we reach the Long Art studio, one of the four art residency studios scattered around Fogo Island. These modern-looking structures, designed by Newfoundland-born, Norwegian-based architect Todd Saunders (also the creative mind behind the Fogo Island Inn), blend seamlessly with the stark landscape. I wonder what it would be like to create in this remote place at the meeting point of ocean and rock.

Joe Batt’s Point Walking Trail runs along the jagged rocky shore past Long Art Studio, one of the four artist residency studio located on the island.

Eventually, we get to the statue of a great auk. This flightless bird once lived in North Atlantic, with the largest colony located on Funk Island 60 kilometres east of Fogo. The great auk held a lot of significance for the Beothuks who’d been living in Newfoundland prior to colonization. Both the bird and the people went extinct around the same time – mid-19th century. Both are a reminder of the devastating impact of colonization and uncurbed greed. The great auk was hunted to extinction by European colonists as a food source and for their down feathers. A cast-bronze statue now commemorates the bird. Created by artist Todd McGrain as part of his Lost Bird Project, it faces a similar sculpture in Iceland where the last known great auk breeding colony was located.

The statue of great auk commemorates this now extinct bird that used to live in North Atlantic with the largest colony located on Funk Island 60 kilometres east of Fogo.

We end the day hiking the Brimstone Head Trail. We take a scenic detour that winds along the coast to the Wishing Well. I root in my camera bag for coins until I find a Ukrainian hryvnia buried in one of the many pockets after my last trip back home. I drop it into the well and wish for peace in our home country. We then climb the stairs to a viewing platform on Brimstone Head.

The Brimstone Head Trail may be short but it packs lots of incredible views.

The sign at the top announces that it is one of the four corners of the flat Earth. It raises a lot of questions. Isn’t the Earth supposed to be round (even if you believe it’s flat)? And if it’s round, how can it have corners? To make matters even more confusing, the map shows a triangle, which definitely doesn’t have four corners. And while we very much believe the Earth is round, we can see why this place would be chosen. With expansive views in every direction, we feel like we’ve arrived at the end of the world, where the rock melts into the ocean and the wind threatens to pick us up and carry over the edge.

No wonder Brimstone Head known as one of the four corners of flat Earth: the feeling of being at the edge of the world is unmistakeable.

Clowns of the Sea

Unlike my very long Newfoundland and Labrador to-do list that required a lot of trimming, my husband’s only had two items: fish and chips at Quidi Vidi and puffins. So on our way to St. John’s we make a detour to Elliston. This small town on Bonavista Peninsula is known for two things: a puffin viewing area and root cellars. In fact, it is dubbed as the root cellar capital of the world. Bonavista Peninsula, along with Fogo Island, was also a filming location for episode 8 in season 2 of Severance, one of our all-time favourite shows, so that’s another reason to visit.

Elliston on Bonavista Peninsula is known as the root cellar capital of the world. It is also the best place to see puffins.

As we make our way down a winding road toward Elliston, we see a whale breech and land in the water with a splash. We drive down to the shore and spend some time watching these ocean giants frolic in the distance hoping they will eventually come closer. They don’t. We then remember why we are here and continue to the puffin viewing site.

We have a few whale encounters during our trip, most of them from distance.

We fell in love with puffins the last time we visited Newfoundland. It’s hard not to. With their huge, multi-coloured beaks and face markings, the way they waddle and flip their short wings, these small seabirds, often called the clowns of the see, are an epitome of cuteness and charm. On our way home, we listen to a puffin episode of our favourite Ologies podcast and learn a lot about Newfoundland and Labrador’s official bird. Atlantic puffin’s scientific name is Fratercula arctica (it means “little brother of the North” and comes from the Latin for “friar” because of their black-and-white plumage). They are part of the auks family (yes, related to the great auk). Puffins mate for life but spend most of the year separated at sea and only reunite on land during a breeding season in the summer. That’s when their beaks acquire those bright colours.

Witless Bay Ecological Reserve down by the coast of Avalon Peninsula is home to North America’s largest Atlantic puffin colony. It is, however, not accessible to the public, and the only way to see the birds is from a tour boat. That’s why a lot of people make a trip to Elliston where these cute birds can be observed right from the shore. Last time we visited, they were congregating on an island a few feet away. This time, the island is so overcrowded that the birds spill over onto the mainland. They waddle along the edge, in most cases oblivious to people, occasionally tapping into their clown identity and posing for the camera. We get lost in watching them for hours until one of us remembers that we still have a long drive to St. John’s ahead of us. Reluctantly, we pull ourselves away from these adorable creatures and get back on the road.

Puffins, often called the clowns of the sea, are an epitome of cuteness and charm.

Small City, Big Charm

After a beautiful but exhausting drive to St. John’s, we finally pull up by a blue, wooden house on Waterford Street. We rented this house because of its proximity to downtown and a deck overlooking the river. Right now, though, the only features we care about are shower and beds.

Our road trips rarely include cities. We prefer to stay away from crowded spaces and sleep on the ground. St. John’s, however, with its relatively small size, beautiful location by the sea and charming looks, is the kind of city we can handle. One of the first settlements in North America, it grew out of a small fishing village. And even though it is now the capital of Newfoundland and Labrador and the province’s largest city, it has preserved its cozy feeling. Part of the charm is its multicoloured buildings. Originally painted in bright shades to make them easier to locate in the fog, the houses, often referred to as Jellybeans, are now one of the city’s main attractions.

Colourful buildings in St. John’s are one of the city’s main attractions.

We start our St. John’s stay at The Rooms, a museum and art gallery that brings a lot of our experiences together. We immerse ourselves in Newfoundland and Labrador’s geological, natural and human history. We try traditional musical instruments, like an ugly stick and spoons and learn more about mummers. Our first introduction to mummers was at the Twillingate-NWI Dinner Theatre where one of the skits featured this old tradition of dressing up in costumes and masks, and visiting from house to house during Christmas time. It reminded us of Malanka, a Ukrainian holiday celebrated on New Year’s Eve, which also involves costumes, masks, house-to-house visits, pranks and performances. It is always fascinating to find similarities between cultures, especially when the cultures are separated by long distances and an ocean.

Music is at the heart of Newfoundland’s culture.

The exhibition called From This Place: Our Lives on Land and Sea weaves together stories of Indigenous peoples – Innuit, Innu, Mi’kmaq, South Innuit – and those of descendants of early European settlers known as livyers, stories rooted in the land, water and those who came before. I find it fascinating but there are missing threads in this story – the Beothuk. This Indigenous group, who lived in Newfoundland long before settlers arrived on the island, are now firmly relegated to the past, pushed to extinction by colonial violence, limited access to traditional food sources, and diseases.

My favourite parts of The Rooms are ᐃᔨ – Eyes collection of wall hangings by Inuk artist Shirley Moorhouse and Silatsualimâk, Anânavut – The Earth, Our Mother sculpture carved out from a fin whale skull by Nunatsiavut artist Billy Gauthier.

Silatsualimâk, Anânavut – The Earth, Our Mother sculpture is carved out from a fin whale skull by Nunatsiavut artist Billy Gauthier.

We end our trip to The Rooms with family photos in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows that offer a panoramic view of St. John’s and the harbour.

“I thought you were mannequins,” calls someone from upstairs as we try different poses, each one sillier than the one before.

The big windows at The Rooms offer great views of St. John’s and a perfect spot for group photos.

We start the next day at Cape Spear. Every morning, this rocky shore sculpted by waves and wind along North America’s easternmost point is the first place on the continent to see the birth of a new day. The air is bursting with pre-dawn freshness and new beginnings as we join a handful of people sprinkled along the edge. The ocean is breathing gently. The sky is streaked with soft pinks and oranges. My husband finds a spot sheltered from the wind where he can make coffee on our trusted Jetboil camping stove. Our younger son ends up in one of Park Canada’s red chairs in hopes of getting some more shut-eye as we wait for the sun to emerge from its nightly swim in the ocean. I look for a spot where I can capture both the lighthouse and the sun. I can hear fellow photographers behind me fawning over the soft pastel colours on the horizon. The red orb makes its appearance to the screeching of seagulls and kittiwakes. A sight that will be witnessed by many people across the continent as the day progresses. I think of Antoine de Saint Exupery’s Little Prince and envy his ability to watch, in his case, a sunset multiple times a day just by moving his chair.

Cape Spear, the easternmost point of North America, is the first place on the continent to see the birth of a new day.

Later that day, we drive to Signal Hill. Sitting above the city at the entrance to the harbour, it used to be an important part of St. John’s defence system, and, as the name suggests, a communication hub. Here, on December 12, 1901, Guglielmo Marconi received the first trans-Atlantic, wireless signal from a station in Cornwall, England. While at Signal Hill, we witness a different kind of communication – the noon day gun. Now a tourist attraction (you can even sign up to fire it, with the help of staff, of course), this very loud tradition dates back to the 19th century when the noon day gun was used by ships in the harbour and St. John’s residents to check their clocks.

Signal Hill is a great place to take in the views of St. John’s. Here, on December 12, 1901, Guglielmo Marconi received the first trans-Atlantic, wireless signal from a station in Cornwall, England.

In addition to its rich history, Signal Hill offers breathtaking views of the city, surrounding hills and the ocean, as well as a network of trails running in different directions. We take one that will lead us to Quidi Vidi to check off the second item on my husband’s to-do list.

Quidi Village is a historic fishing village that is now part of St. John’s. Here, small fishing huts on stilts cling to the rock along the water’s edge, across from Quidi Vidi Brewery, famous for its Iceberg Beer. It is also home to Quidi Vidi Village Artisan Studios.

Quidi Vidi is a charming fishing village where you can get the most delicious fish and chips.

The fish and chips truck that used to sit by the brewery is no longer there. I can see disappointment written all over my husband’s face. Luckily, there are a few other food trucks, one of which is called “Sea treats” so we decide to give it a try. In addition to fish and chips, they serve lobster rolls, scallops and other delicacies, and the food is delicious. With each bite of cod, the disappointment slowly melts away. Mission accomplished! We can now head back to Signal Hill.

The day ends with a stroll on Water Street. We grab coffee and treats at our favourite Rocket Café before heading back to the house to prepare for our backpacking trip on the East Coast Trail.

The Spout

With the comforts of the city behind, we lace our hiking boots, hoist our backpacks, grab walking sticks and set out to conquer the East Coast Trail. Well, a small section of it because the entire East Coast Trail is 336 kilometres long and requires way more time than we have left of this trip. The trail runs along the coast of Avalon Peninsula from Cappahayden in the south to Topsoil Beach in the north. It passes many communities along the way, including St. John’s, and ventures into remote areas, through the woods, barrens and bogs, past cliffs, sea stacks, waterfalls and caves.

The 336-kilometre-long East Coast Trail runs along the coast of Avalon Peninsula.

Some people explore the trail one section at a time, doing day hikes and staying in local communities along the way; others choose to backpack and camp in its remote areas. During our trip, we meet a couple of friends on day 11 of their trek from Cappahayden to St. John’s and a woman who is planning to complete the entire trail in twelve days. We also run into a large group of day hikers coming back from the Spout. There are several ways to access this geological feature and each one means more than 20 kilometres of hiking. Considering that most people in the group look like they are in their 60s and 70s, that’s quite an accomplishment – #LifeGoals.

We too are heading to the Spout. Instead of doing it as a day hike, though, we decide to turn into an overnight, or rather two-night, trip. Our initial plan was to hike from Cape Spear down to Bay Bulls but that required more time and someone to drive us back to the starting point. We then considered camping at Little Bald Head campground for two nights and spending the second day hiking the rest of the Spout Path and part of the adjacent Motion Path. In the end, we scale down even more because of our younger son’s issues with his knee. Also, because of that new relaxed approach to our trips I talked about in Part I.

This is not our first encounter with the East Coast Trail. When we first visited Newfoundland eight years ago, we did a short part near Cape Spear and somehow were under the impression that it was not that hard. Different paths, of course, have varying degrees of difficulty, and the Spout Path is one of, if not the most challenging section of the entire trail. So that assumption is about to be blown up into smithereens. At first, though, it is fairly easy: a few ups and downs, nothing too arduous. Beautiful views and an abundance of blueberries along the way help.

Propelled by beautiful views and blueberries, we take on the Spout Path of the East Coast Trail.

We pass the Bay Bulls lighthouse, have lunch near the Turn of the Bald Head. After that the trail takes a turn – an upward one, climbing steadily through the woods and low brush – then veers back down to the coast. After 11 kilometres of hiking, the Little Bald Head campground comes as a welcome sight.

Campground is probably too big of a word for this small patch in the woods with 11 closely packed campsites (seven of them with wooden platforms) and a primitive outdoor toilet. A bit about that. Doing a lot of backcountry camping in Ontario, we are used to thunderboxes – simple wooden boxes with a hole and a lid (the thunder part is inspired by the sound the lid makes when dropped down). In Newfoundland, backcountry privies look more regal: these circular structures with a raised back and sides bring to life that famous euphemism for a toilet – although in this case a plastic throne, not a porcelain one.

One of the sites is already occupied when we arrive. A few of the platforms are nestled amidst brush and trees. We opt for two that are located more in the open slightly further away, even though further away is a relative concept here where sites are an arm’s reach from each other. Luckily, the campground is not busy. Two other sites end up being occupied on the first night, only one on the second.

The Little Bald Campground has 11 campsites, seven of them with wooden platforms.

The next morning, my husband and I wake up at 4:30, pack our coffee paraphernalia and my camera, and head to the Spout a little under a kilometre away. By now you are probably wondering what it is, so let me explain. The Spout is a wave-powered geyser. Water from the river drains down a hole into a cavern below where the pressure from the waves pushes it back up into a cloud of mist. The frequency and size of the puff depend on the waves, and as luck would have it, we arrive on a calm morning. Still, it is a cool phenomenon, and we have a lot of fun exploring it.

When we arrive at dawn, the coast is serene and eerie. A group of seagulls is splashing in a small pool of water on the rocks. We call it public baths. The sun takes its time emerging from behind a gauzy strip that has stitched the sky and the ocean together. Eventually, the red orb makes an appearance and repaints the world around. No matter how long I’ve been taking photos, I never cease to be amazed by the beautiful glow of the morning light.

Sunrise on the East Coast Trail is a magnificent sight.

We later return with the kids and spend the day around the Spout. We climb rocks, find the entrance to the cavern that powers the geyser, watch white and brown discs of jellyfish bob in the water. We stick our heads above the Spout and feel its misty freshness on our faces. I imagine this is what dogs must feel like when they stick their heads out of a moving vehicle. It ends up being one of our favourite days on the trip.

We spend hours exploring the area around the Spout, a wave-powered geyser.

After another night at the Little Bald Head campground, we retrace the trail back to the starting point. Even though, it is supposed to be easier going this way, somehow it feels longer. By the time we are done, we hanker for fish and chips, so we hop in the car and drive to The Captain’s Table restaurant in Witless Bay.

“You look hungry”, a waitress comments at the speed with which we order food.

“Just finished the Spout Path,” we smile. The food never tasted better.

On the left: How we feel at the start of the hike. On the right: How we feel when we finish it.

The Edge of Avalon

Imagine an ancient community buried under ash. No, not Pompei. I am talking about Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve. This southeastern point of Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula contains the world’s largest fossil site of the oldest, complex organisms. These soft-bodied creatures used to live deep under the ocean 580 to 541 million years ago. That was millions of years before animals developed skeletons and hard shells, the parts that are normally preserved as fossils, so there are few remains of these organisms. However, because the life-forms at Mistaken Point were suddenly buried under volcanic ash, the imprints of their soft tissues have been preserved in mudstone and sandstone. More than 30 species can be found at Mistaken Point, most of them belonging to extinct groups.

“Think of them as a community, not individual organisms,” says one of the tour guides as they lead us onto the fossil beds, making us take off our shoes first. The only way to see the fossils is with a tour. Two tours a day are offered in the summer, each one limited to 12 people. Good thing we booked our spots early.

Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve contains the world’s largest fossil site of the oldest, complex organisms. The only way to see them is as part of a guided tour.

We potter around the two fossil beds open to the public in our socked feet just as it starts to rain. The guides take us back to the time when complex life-forms started to emerge. We learn the names of various creatures and hear about the fascinating process of reconstructing their looks based on the imprints. One of those names – Fractofusus – gets lodged in my husband’s head and he keeps repeating it like a spell for the next few days.

Imprints of more than 30 species of soft-bodied life forms that used to live deep under the ocean 580 to 541 million years ago have been preserved under volcanic ash at Mistaken Point.

The guide shows us a spot where a chunk was removed from the fossil bed, most probably sold on the black market. I am surprised to learn that there is a black market for fossils.

“I’ve been coming here every year since I was eight,” says the guide. “This piece was already missing back then. As a kid, I had a persistent fantasy that I would find it and bring back here where it belongs.”

Once the tour is over, we continue along a gravel road to Cape Race National Historic Site. It is home to Cape Race Lighthouse, one of the world’s most powerful land fall lights thanks to one of the rarest and largest lenses ever made – a hyperradiant Fresnel lens. It has been in operation for over 160 years and is still manned year-round. Here, the Marconi Wireless Station was the first to receive a distress call from the Titanic.

Cape Race Lighthouse has been in operation for over 160 years and is still manned year-round. It was the first place to receive a distress call from the Titanic.

We drive back to Edge of the Avalon Inn, where we stayed the night before, for lunch and then continue along the Irish loop to St. Bride’s, our final destination of the trip.

We stop at St. Vincent’s Beach along the way known as the Whales Playground. Here, the majestic ocean creatures come so close to the shore you can practically touch them or hear them breathe, depending on which brochure you read. We keep our fingers crossed for this last opportunity to see whales up close. Alas, all we find are a few loons bobbing in the water and a bunch of humans on the shore peering into the distance. We wander along a cobblestone beach looking for cool rocks, then with one last look at the ocean, turn back to our car. We pass an old man reading a book in a camping chair at the end of the beach, a bicycle propped next to him.

“You are two weeks too late,” he says when we express our disappoint about not seeing the whales. “They arrive every year in June without fail, then retreat in mid-July. They are still out there, just don’t come close.”

We make a mental note to start our next trip on this side of the island.

“You should have seen this place earlier. This whole beach packed with people. The whales swimming right here, diving, breeching, fins, tails – quite a spectacle,” he adds.

We later joke that maybe it’s the other way around: whales come here to see humans because they know we flock to this shore in June and early July.

St. Vincent’s Beach is known as the Whales’ Playground. We are too late to see these ocean giants.

We approach St. Bride’s as the sun starts to set. From the top of the hill, we see the road in front of us disappear into the ocean, a glowing orb at the end of it like a pot of gold. There is no good spot to stop for a photo, so we watch the sun slowly sink into the water as we drive along a potholed road. Some sunsets are meant for memory alone. By the time we reach Capeway Inn, the skies are crimson red.

Our last day in Newfoundland is hot and sunny. We walk down a trail at Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve. It winds along the coast to Bird Rock, the most accessible seabird rookery in North America and home to gulls, razorbills, common murres, black-legged kittiwakes, northern gannets, and double-crested and great cormorants. We hear them before we see them. A growing racket fills the air – a cacophony of cackles, screeches and squawks. A rocky island just a few feet away from the shore and surrounding cliffs are alive with birds – flapping their wings, fighting, feeding their young (which is quite a sight when it comes to northern gannets when those fluffy grey babies dive deep into their parents’ throats looking for fish). The ocean below is dotted with bobbing silhouettes; the sky is whirl of wings and tails.

Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve is home to gulls, razorbills, common murres, black-legged kittiwakes, northern gannets, and double-crested and great cormorants.

It is a beautiful spot to wrap up our trip and say goodbye to Newfoundland, a place we’ve grown to love so much.

We end the trip on a high note.

Ferry

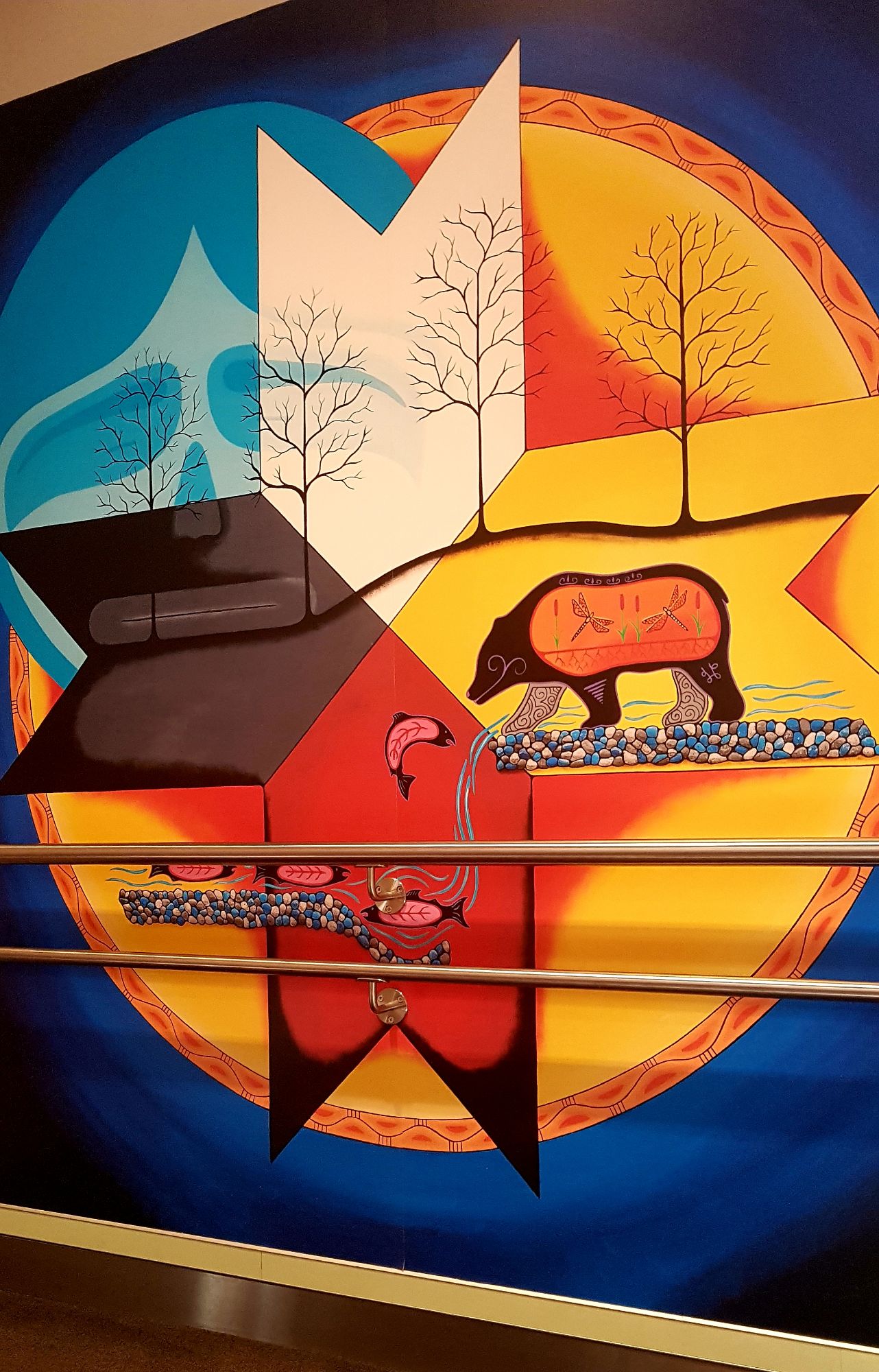

On our way home, we decide to take a ferry from Argentia, instead of Port aux Basques. It saves us from driving back to the west coast but adds to our sailing time. The vessel is called Ala’suinu, which means “Traveller” in Mi’kmaw, and features artwork by Indigenous artists and photos of Newfoundland and Labrador throughout. The services are much better than on the ferry we took coming here, we even get a live performance. We joke that it is as close as we will ever get to being on a cruise. Most importantly, we manage to get two pods, each one with a set of bunk beds, which means a night of comfortable sleep before we get on with our two-day drive to Toronto.

On the way back, we take a 16-hour ferry from Argentia on the vessle called Ala’suinu, which means “Traveller” in Mi’kmaw.

We wake up early to watch our last sunrise of the trip. Sunrise at sea – with nothing but water and air around, no solid ground to anchor your gaze – feels like the birth of the world. With all the trips to the past we’ve got to experience during our travels, this one takes us further back, even if just in our imagination – back to the time before continents, before rock and soil, back to the fluid, malleable, shifting world made of liquid, gas and infinite possibilities.

Sunrise at sea feels like the birth of the world.